Cynical English Class With Professor Ben

First things first: I’m not a professor. I’m not an educator of any kind. I have a bachelor’s degree in Computer Science, and I’m not even particularly good at that. Take everything I say with a grain of salt. I understand that there are sensitive issues wrapped up in what I plan to talk about, and I very much want to have a discussion about them. I’m not trying to tell anyone what to do. So, with that out of the way…

Every few years, the subject of book banning in high school English classes comes up. To be clear, the “ban” in the cases that I am discussing has been an administrative or school board ban on teaching these books. Students are still allowed to read whatever books they want on their own time. Often, the “banned” books in question remain in the school libraries. The ban simply refers to an administrative decision not to allow or require certain books to be taught in English classes. I unequivocally do not believe that anyone should be prevented from reading any book; however, my opinions regarding which books should be taught are less absolute.

The reason given for these “bans” varies, but the one I’ve heard most commonly in recent years is that the school received complaints from students and/or their families regarding the racial slurs used in some of these books. Despite these books having anti-racist messages, some administrations have decided that they can teach the same lesson with different books that don’t use the offending language. For many, the idea that To Kill a Mockingbird, Huckleberry Finn, or Of Mice and Men being too offensive to teach is political correctness gone wild. I don’t happen to agree, but I also think that there are a few questions we need to answer before we can really dive into the politics.

What is the point of a High School English Class?

In our recent episode on The Chocolate War, Nate and I joked that high school is basically just daycare for teenagers. More seriously, I think that the goal of high school is to prepare students for living and working in the adult world. If I’m being honest, I don’t think that having required fiction reading is the best way to prepare a child for the “real world.” This is anecdotal, of course, but in my personal experience, I’ve spent dozens of classroom hours across multiple years reading and analyzing To Kill a Mockingbird. If the goal was to prepare me for entering the real world, then I wish we could have carved out some time to talk about filing income taxes. Maybe we could have had a unit on the difference between a 401k, IRA, ROTH IRA, Mutual Fund, etc.

When I ask people what they believe the purpose of high school English classes are, I get two kinds of answers. The first kind is practical and simple: literacy. There is no career a modern adult can have in which the ability to read and write proficiently will not be beneficial. This is a good answer, but it doesn’t line up with my personal experience in a classroom. As I’ve said before, I have a degree in Computer Science. The bulk of my written communication is technical writing and email. My formal education covered precious little in these areas. Over the years I’ve helped many friends write cover letters and resumes. Too many high school graduates are not prepared to write a professional e-mail, resume, or cover letter. They did pretend to read Of Mice and Men for 6 weeks, and then they wrote a 10-page double spaced essay on it, though, for whatever that’s worth.

The second answer to my question is more philosophical and esoteric. I’ve been told that point of English class is to “broaden one’s horizons.” It’s to foster a lifelong passion for reading. In general, the goal of reading fiction and writing essays is to make students more thoughtful, well-rounded individuals. This leads me to ask two further questions.

Are books always the right tool?

At this point in the essay you may be asking yourself why I even bother producing a “book podcast.” Obviously, I want people to be excited about reading fiction, and of course, I think that reading fiction can be a great way to broaden horizons. I do hope the irony isn’t lost on anyone, though, that I choose to express my passion for books through an audio medium. This blog reaches a fraction of the audience that the podcast reaches. The podcast, in turn, reaches a fraction of the audience that a Youtube channel would reach. There are reasons for this. Reading demands more of a person than other forms of media consumption. This is a blessing and a curse.

Reading engages with the brain in a very particular way. It requires the reader’s active focus. In fiction reading, in particular, the reader must decipher the symbols and then conceptualize that information in their mind. It takes very real mental effort. It is harder to get started reading than it is to get started with a movie, video game, or song. This forced engagement can mean that the reader is primed to think more critically about what they are reading than what they consume more passively. Unfortunately, this means that reading something you hate can be unbearable torture. Just ask my co-host. None of this takes into account the variety of personality-types and different physical/intellectual needs that can make required reading incredibly difficult for some.

It’s always seemed to me that what we’re really trying to encourage is exposure to new ideas and different perspectives, followed by critical examination. The full spectrum of creative work is available to us. I think there is a good argument to be made for teaching the critical consumption of more than one kind of media in our schools. Most people get most of their information from sources other than books. I didn’t have classes on film literacy or music literacy until college. Interestingly, both of these courses borrowed the term “literature” to describe the subject matter: “Film as Literature” and “Music as Literature.” No matter what media we teach, though, we’re going to run into another problem.

How do we determine which works to teach?

The first thing that should be considered is that the overwhelming majority of students in a high school English class do not do the assigned reading. It’s difficult to find hard data on this. I suspect that’s because most people have zero incentive to admit to cheating. In the absence of good studies on the topic, I’ve turned to the blog-writer’s oldest and dearest friend: anecdotal evidence. I’ve asked just about everyone I know if they did all of the assigned reading in their high school English classes and I received a nearly unanimous: “No.” Even among diligent students who wanted to engage with the material, summaries and notes that were freely available online proved too tempting. Time is a precious commodity. If I’m going to spend 5-10 hours per week reading, then it will be spent reading something I enjoy. Or, as it often happens, something for this podcast.

At first, the simplest solution would seem to be letting the students choose the books they want to read individually and having them write a paper or something. The trouble with this is that it limits the ability of students to discuss the book with their peers, and their teacher. If our goal is to get kids to think critically about new ideas then we need to have discussions. Those discussions are much easier if we all share the same material.

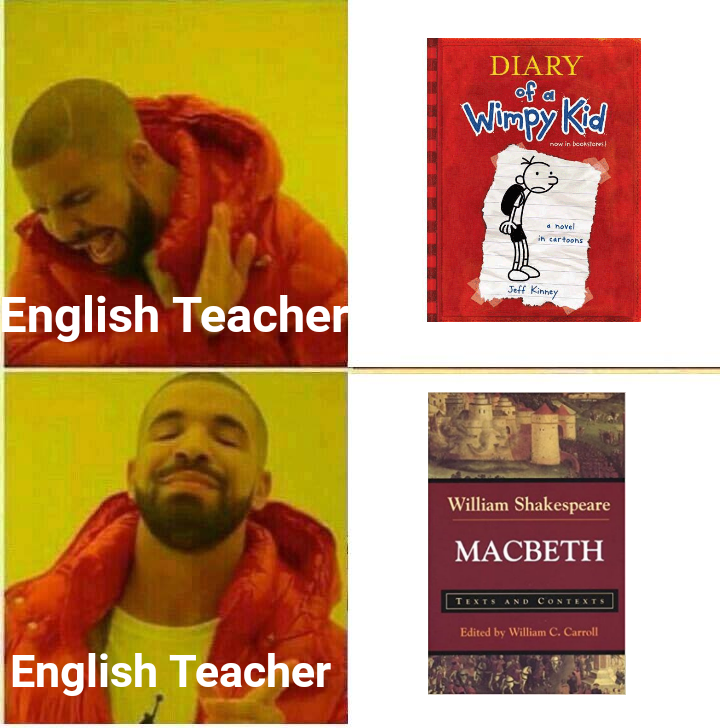

If we want to have group discussions about the material, then we need to choose material that has broad appeal. The catch here is that things that have broad appeal aren’t often very challenging. The more challenging material is, the more likely it will be to turn a person off.

I don’t really have a good solution to this problem. My personal solution has always been to join a book club. That’s kind of how Words About Books was born. Maybe students can be separated into smaller groups based on which of a set of predetermined options they would like to read? I don’t know how feasible any of this is in a modern classroom. I’m not a teacher, and I’m not familiar with all the restrictions that go into trying to innovate new lesson-styles. That brings me to my final point.

If you’re not an English teacher or an English student, don’t worry about it.

I said before that I asked a lot of people if they did the assigned reading in English class. I also asked a lot of people if they thought specific books should be taught in English class. To my surprise, this had a much wider range of answers. Some people had very strong opinions that certain books must be taught, or that they wished that they had read the book when it was assigned to them. Some people didn’t care one way or the other. Some people wished they could have gotten credit for books they wanted to read.

I don’t understand how one can have strong opinions about what books children should read, while simultaneously knowing what it is like to be a child who is forced to read something. Like so many things in this country (America) this seemed to come down to politics. It wasn’t really the book that they felt should be taught, it was the message that they perceived the book to have. There seems to be this line of thinking that if a child reads a certain book then they will develop “correct” world views.

Allow me to assure you that this is not true. I have certainly read books that have changed my life. I’ve read books that have made me rethink long held political views. I’ve also watched youtube videos that have made me rethink long held political views. Being forced to read Fahrenheit 451 in high school, take tests on the events of the book, and write essays where there was very much a correct response, did not do a good job of making me engage with the book’s themes. In fact, it made me think that Ray Bradbury was an incredibly boring author. An opinion that an older, wiser, and more well-read Ben would slap my younger self for having.

In my experience, most teachers teach the way they do not because they think it is the best way to teach, but because it is the way that they must teach. This really isn’t benefiting anyone. Good teachers know their audience. If they don’t think that a particular book is going to work for their class, then I’m inclined to trust them on that. I wouldn’t tell a biology teacher how to teach biology just because I dissected a frog one time 15 years ago. I don’t think we should be telling English teachers which books they have to assign just because we adults pretended to read them decades ago.