What is a Donkey Kong?

Believe it or not, most of us have been engaging in ontological debates since we were children. Ontology is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of being. Basically, ontologically looks to find out what exists, what is real, is it all one big thing or is it a bunch of discrete things. When your least favorite friend develops a passionate opinion about whether or not a hotdog is a sandwich, they are making an ontological classification. This annoying, probably theater-child, has made several assumptions. They assume that there exists a thing called “sandwich” and it has certain properties. There also exists a thing called “hotdog,” and hotdog also has those properties and therefore a hotdog belongs to the more general classification of sandwich. In the oh-so-hilarious debate that will no doubt ensue, participants will be forced to examine all aspects of these assumptions, for you see, when many people think of “sandwich,” they do not think of something that looks like a hotdog. If you’re bored enough or pedantic enough to sit down and try to explain why that is, then you might just have the makings of a Douche Philosopher.

I recently found myself in just such a situation as I was forced to classify what is and is not a “Donkey Kong Game.” Like with that dumbass sandwich thing, there are many underlying assumptions about the nature of reality baked into this question, and my least favorite co-host thought it would be fun to explore them. In the moment, I’ll admit I kind of phoned it in. It was late. I’d just walked 2-miles. I wasn’t on the top of my game. But now I’m rested, caffeinated, and ready to really douche it up. So let’s philosophize properly.

Unless you have lived under a rock for the last 40-years, you probably have some conception of what Donkey Kong is. If asked to define Donkey Kong, a reasonable description would be: a cartoon gorilla featured in many Nintendo properties. Unfortunately, that definition would also apply to Dixie Kong, Diddy Kong, Funky Kong, Lanky Kong, Chunky Kong, Cranky Kong, Candy Kong, Tiny Kong, Kiddy Kong, Swanky Kong, Bluster Kong, Baby Kong, Manky Kong, Sumo Kong, or Ninja Kong. There might be more. I don’t care. Let’s define Donkey Kong instead as: a cartoon gorilla featured in many Nintendo properties explicitly named “Donkey Kong.” This narrows it down a little more.

In the earliest incarnations, Donkey Kong was imagined to be an abused pet gorilla kept by Mario. In a sequel game the title character was instead said to be the son of the original Donkey Kong, also named Donkey Kong, who was trying to rescue his father. There are now at least two entities named Donkey Kong that look pretty similar. Future, more story-driven games would muddy the backstory. Nintendo, originally seeing Donkey Kong as a monster, now wanted to make him a hero…and they also wanted to walk back that Mario animal abuse stuff. It is unclear if the modern Donkey Kong is meant to be a direct continuation of the original, and it might not even matter. After all, most people are able to recognize Donkey Kong without knowing anything about his backstory or even that a backstory exists.

Plato’s a pretty big deal in the philosophy world, and he had an idea about reality. Plato thought that there existed a world of Forms in which the perfect, unchangeable essence of all things existed. Everything in our world is an imitation or representation of its True Form. Everything in our world changes and decays. Only in the pure unchanging world of Forms can things be perfect. Multiple instances of a form can exist in our world.

According to this theory there exists a Platonic Donkey Kong. The True Form whose magnificence we can but glimpse in the shadows it casts on our ever-decaying reality. Our eyes cannot perceive the entire Truth of this form as we always glimpse it in a state of change. We can, however, recognize that it is a shadow of Donkey Kong. Plato says that we must see with our minds, not with our eyes to understand the reality of Donkey Kong. Well, I mean, he didn’t say Donkey Kong specifically, but the principle is the same.

When we see the abused pet of Mario, we see Donkey Kong. When we see the heroic slayer of kremlins, we see Donkey Kong. When we see Cranky Kong, we see Donkey Kong. Like all the best worlds, the World of Forms is strictly hierarchical.

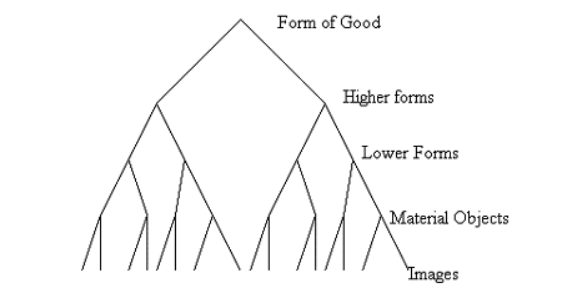

Plato believes that all forms descend from the ultimate form of Good. There are higher forms representing ideals and lower forms representing perfect materials and objects. Beneath those are the forms which make up our material world. Beneath even that lie our representations of the material world. I would argue that all Donkey Kong side characters are lower orders of the sublime Donkey Kong Form in this hierarchy. Cranky Kong is just “Donkey Kong but old”, Diddy Kong is “Donkey Kong but young”, Dixie Kong is “Donkey Kong but girl”, and so on.

Donkey Kong is a character, a video game genre, a setting, and much more. The Platonic Donkey Kong is ultimately unknowable and indescribable. According to Plato, all of these things are distortions of the primordial Donkey Kong, which is itself one aspect of Ultimate Good. Does this mean that all of the games we discussed are Donkey Kong games because they are all shadows cast by the Platonic Donkey Kong? Or does it mean that none of the games we discussed are Donkey Kong games because the true Donkey Kong cannot be present in the decaying world of the material? Am I Donkey Kong? Are you me?

Now that I think about it, what even is a “game” in the context of this discussion. Merriam-Webster’s dictionary defines “game” as “a physical or mental competition conducted according to rules with the participants in direct opposition to each other.” I don’t love this definition because most Donkey Kong Games don’t even fit into it unless we really stretch the definition of “participants.” Let’s say that a game is a form of play guided by clearly defined rules and boundaries. Let’s go a little further and say that a video game is a form of play guided by clearly defined rules and boundaries that are enforced by and presented to a player or players by a computer program.

To a large extent a game is its rules. The original Donkey Kong game is a collection of game mechanics with graphics depicting a cartoon ape antagonist and suspiciously-mario-like player character. The antagonist throws barrels at the player character who must carefully climb ladders to avoid the barrels and other obstacles to reach the top of a maze and save the girl that the ape has kidnapped. The graphics and the music are largely arbitrary. We could replace the barrels with fireballs, the ape with a wizard, and the player character with a medieval knight and we would still be playing essentially the same game. In fact, many people didn’t even see a need to replace the ape. Would a game reskinning the original Donkey Kong game still be a “Donkey Kong game?”

Is it the aesthetic character and world of Donkey Kong or the game named Donkey Kong that carries the true essence of Donkey Kong? Is it the blessing of the official rights holders of the name “Donkey Kong” that makes something a Donkey Kong game? This is easier to answer. Legally speaking, yes.

Here’s the deeply frustrating thing about ontology. There are no objectively correct answers to these questions, but also the answers to these questions can have a huge impact on our lives. The Donkey Kong Intellectual Property is worth millions, if not billions, of dollars. What is and is not a Donkey Kong game is a very real legal question with a very real legal answer. Attempting to argue that point and losing can have very real consequences. To answer the question “is this Donkey Kong” we also need to know who is asking and why. I personally subscribe to the belief that the distinction between things is at least as dependent on the perspective of the observer as it is on the object being observed. We decide, as a society, what is a Donkey Kong game.

When we play these ontological games of “is thing a category,” we’ll eventually come to a point where our answer exposes our reasons for establishing the category in the first place. There is no universal conception of “sandwich” or “donkey kong” that originates from on high. We made these categories up because it was somehow beneficial to us to differentiate one thing from another. We, as a culture, come to a general consensus on what certain terms mean and if the context can change the meaning of the terms. We are constantly renegotiating terms and context. Depending on the term in question, this can have deadly consequences.

I guess all of this is to say, never be too sure that you know what anything is, especially a hotdog.