This Post Is Filler…or is it?

I have challenged myself to write 1 small essay relating to our weekly discussion on Words About Books. I probably should have waited until Nate’s Nightmare November ended before starting this challenge, but in my infinite naivety, I didn’t think it would be a problem. No one told me we would be doing 3 episodes on Hulk Hogan and 2 episodes on Naruto. I’ve been racking my brain to try to come up with topics for essays on these “books.” I used up all my sincere and thoughtful material on my last essay about falling out of love with the shonen battle genre. The muse has fled. I’m sure that given more time, I would be able come up with something, but the essay is due this week!

That’s when it hit me, dear readers. What I needed was filler, and who knows more about filler than serialized manga artists? And what better to cover in a filler post than filler itself? How meta. How delightfully ironic. Now, I must admit, I have done exactly this before on other podcasts; but, just because it’s been done before doesn’t mean it can’t be done again in a slightly different context. So just like a beach episode, a trip to the hotsprings, or a tournament arc, I ask you once again, dearest readers, what is filler?

Nate actually said something interesting in the Naruto episode that I let slide because I wanted to avoid this very discussion and, hopefully, end the episode as soon as possible. He said, “…then we have some filler…” To which I replied, “I thought you were reading this.” He confirmed that he was reading it, and that he meant that it was a “filler chapter.” I realized in that moment that he and I had different definitions of what it means for part of a work to be “filler.”

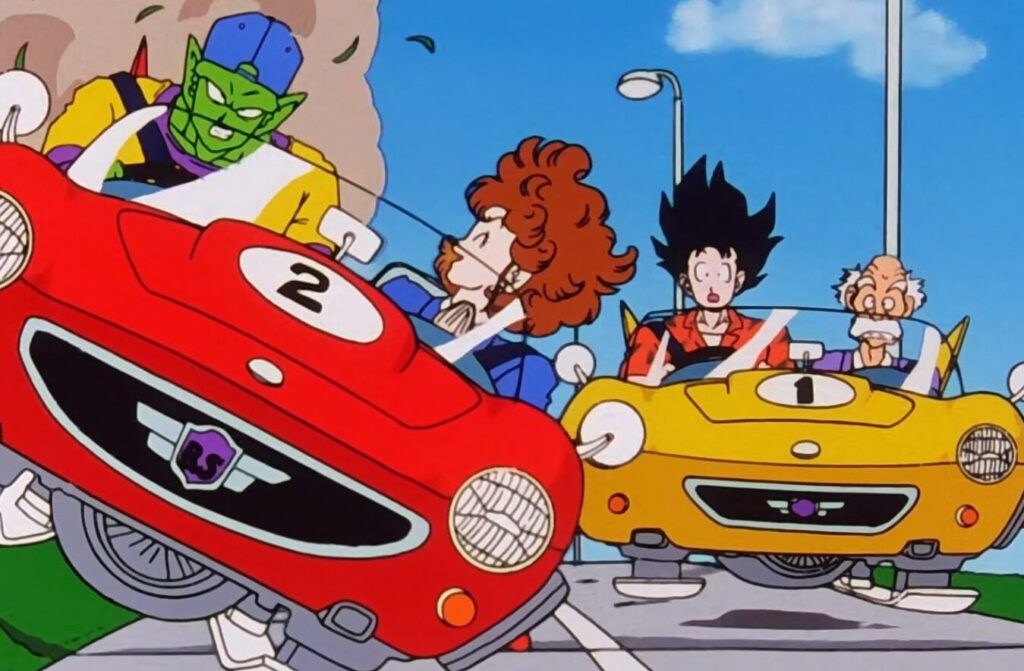

In the context of my favorite shonen battle manga, Dragonball Z, it is common to refer to storylines and characters that exist only in the anime as “filler.” Toriyama did not write this material. The studio was adding it because they needed to “fill” time because the anime production was constantly in danger of outpacing the source material. In this sense, the word “filler” is loaded with an additional connotation of “non-canonical.” Under this definition, it is logically impossible for Akira Toriyama to create Dragonball filler.

This is why I found it jarring when Nate referred to Masashi Kishimoto’s own work as filler. It took me a moment to remember that, for Nate, the word “filler” had no connotations of canonicitiy. For Nate, filler simply refers to material that is added or stretched specifically to buy more time for the author to develop the “important” parts of the story. This may seem like a logical definition but it begs the question (and yes, I’m using that phrase correctly): how do you know this material isn’t an important part of the story. My colleagues over at That Time I Got Reincarnated In The Same World As An Anime Podcaster introduced the terms “fluff” and “futz” to try to remedy this misunderstanding regarding “filler.” After thinking about this every day for the 3 years since that episode has aired, I’m not so sure that more words is the answer (ironic, I know). Labeling content as fluff or futz brings us back to the same problem: who is the judge of which parts of a text are fluff and futz.

We know that some episodes of serialized media will be mediocre as a sacrifice to the budget and schedule. It is easy to assume that anything we find boring or unsatisfying is a result of this need to maintain consistent production. I’m guilty of exactly this. I’ve been making more of an effort to read light novels, which tend to be published in serial fashion before being collected into volumes. In our episodes on the Beware of Chicken novels, I made just such an assumption. I assumed that one reason for the ever-ballooning cast was that many characters began as a form of filler. My reasoning went that when the author was stuck on a particular plot thread he would change perspectives or invent a wholly new character to give himself time to develop the problem-thread. After releasing those episodes, the Beware of Chicken community (who are actually incredible) let me know that they disagreed with some of my assessments. Some of these characters apparently go on in newer chapters to become very important and main-plot-relevant.

This doesn’t really change my opinion about the writing strategy that Casualfarmer employed, but it raises some interesting problems for our attempts to separate a text into it’s fluff, futz, filler, and “important” parts. People can disagree on what is important. This prompts another layer of deconstruction in which we find that these labels are also loaded with an another connotation: authorial intent. Readers are able to guess with some degree of accuracy which parts of the story the author planned from the beginning, which parts of the story were figured out in the process of writing, and which parts of the story were added purely to meet a deadline. But the reader can never be certain of this unless the author is very aware of their own process, and is willing to share detailed information about it. Few authors are likely to admit to creating “unimportant” chapters or episodes. Even if they did, in the case of Casualfarmer, what if something that started as an unimportant detail inspires a more interesting and important aspect of the story later on.

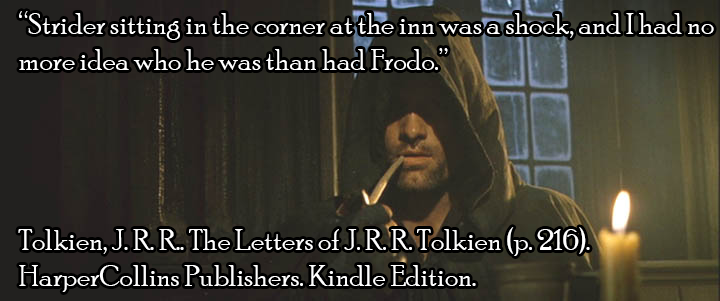

In Letter 163, Tolkien talks about his writing process. Interestingly, he focuses in on the Bree sequence. The Hobbits arrive in Bree to find that Gandalf is not there waiting to meet them. Gandalf is the organizer of this whole scheme. He is the only one who has the larger picture of the threat to Middle Earth and the more immediate threat to Frodo. The group encounters a mysterious stranger whom the locals call Strider. They choose to trust Strider. He is able to lead the party safely to the next phase of their journey. Strider, as it turns out, is none other than Aragorn, son of Arathorn, heir-in-exile to the thrones of Arnor and Gondor, one of the last of the Dunedain, descendent of elves, men, and maiar. This is one of the most important characters and one of the most pivotal moments in the entire saga.

In the letter, Tolkien informs us that none of this was planned. He discovered that Gandalf was missing while writing the chapter. He didn’t know who Strider was. The process of writing was necessary to figuring out the story. Tolkien needed to be able to explore the minutia of getting from Point A to Point B before he could say for sure what was important. In the process, the connective tissue became as important, sometimes more important, than the “plot” as he’d initially concieved it.

Tolkien died without completing his Silmarillion. The Silmarillion was a collection of myth and saga, primarily concerning the elves, from the early days of his “secondary world.” Christopher, his son, completed the work to the best of his abilities, but questions about his choices arose. Tolkien scholars (Yes, that’s a thing. No, I don’t qualify. Yes, I’m angry about it.) were unsure about some elements of the mythology that were previously ambiguous that Christopher solidified, perhaps the most famous being the creation of the orcs. Christopher, a specialist in ancient mythological and heroic texts by trade, took a scholarly approach to explaining himself. He published nearly every line of text his father ever scribbled, wrote, or typed about the mythology in a series called The History of Middle Earth. This included detailed annotation and commentary explaining Christopher’s process of trying to follow his father’s, often disorganized, thoughts on the legendarium.

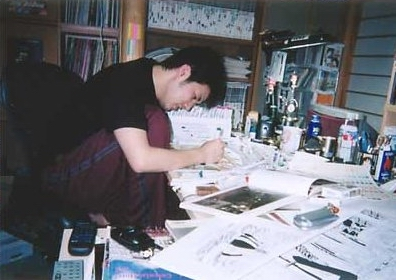

Tolkien was a serial drafter. He was working in the age before computers, so there was no copy paste function. Each time he wanted to rework his text he needed to start with a fresh copy. He wrote and rewrote the legends, poems, and narratives of the old world for decades, continuing the process until the day he died. This is also how he approached the Lord of the Rings. Writing and rewriting chapters until he was satisified. If something needed to be added to the Two Towers that had implications for Fellowship of the Ring, that could trigger a total rewriting of several chapters. The end result was a product that was obsessively edited, each line carefully considered.

Tolkien would certainly say that there is no filler in Lord of the Rings. I would also say that there is no filler in Lord of the Rings, but I know that plenty of readers are laughing out loud right now. They’re probably imagining paragraph long descriptions of mallorn trees or light reflecting off lakes. These are things that readers consider unimportant, but that Tolkien considered to be very important.

Tolkien did not publish Lord of the Rings one chapter at a time. He had the relative luxury of obsessing over each line of his work and ensuring that it was cohesive and logical at every step of the journey. As stated before, mangaka work in different conditions. These conditions will naturally create problems for the cohesion and logic of the narrative. I’m going to risk an unpopular opinion here: the conditions many mangaka work under aren’t conducive to good story telling.

While we may dance forever around a proper ontological definition of “filler,” we can maybe make a little progress by examining our motivations for seeking a definition in the first place. On some level I think labeling things as filler, futz, or even fluff, is an attempt by fans to provide much needed editing to a work that feels bloated and inconsistent. At the time of writing, the manga One Piece is approaching nearly 1200 manga chapters and nearly 500 hours of animated television and films. At a certain point, the sheer size of the work becomes a barrier to entry for fans who have not been steadily consuming it over a period of decades. Fans of One Piece have produced guides on which elements of the story are “filler,” and therefore, can be skipped.

The conversation of filler comes up very frequently in long running serialized fiction community’s, because so much of it is simply not “the good stuff.” It falls to the readers and viewers to edit a bloated work on behalf of the artists. As a result, the question of “what is filler” is, unfortunately, as relevant as it is unanswerable. Anyone who consumes the fan-abridged (not referring to comedic dubs, but rather to recommended watch/read orders) versions of the series is submitting to the community’s interpretation of what is important in the text. If you read a fan-abridged Lord of the Rings, you may be encouraged to skip chapters like “A Shortcut To Mushrooms.” Many people don’t consider Farmer Maggot to be a particularly important character, but the author did. He wrote that chapter for a reason.

In the process of writing this blog post, I feel myself coming to an interesting and unexpected conclusion. I don’t think that any of it is filler. Acknowledging the realities that some chapters of a serialized story will receive less effort and attention, I still don’t think we can make the decision to exclude them on that basis or any other. They are all important to the construction of the narrative. There is no filler, no fluff, no futz. There is only text.

One Piece feels bloated and inconsistent because One Piece is bloated and inconsistent. We can factor in the working conditions of the writer when we decide how harshly to judge the overall work; but we can’t just throw out material that we think doesn’t need to be there when judging the overall work. I’m beginning to think that third-party editing/abridging efforts are actually the creation of a derivative work, artistically if not legally. A human being, other than the artist, is adding their vision and perspective to it even if they are only deleting. When art is put out into the world it can’t ever be drawn back. If your anime adaptation contains hundreds of hours of bloated nonsense, that can’t be erased. That happened. Dragonball Z Kai is not Dragonball Z. It is a similar, but new, derivative work based on an editor’s opinion of what Dragonball Z should have been.

And if that’s the case…then maybe this post isn’t filler either…maybe it’s just a bloated mess…