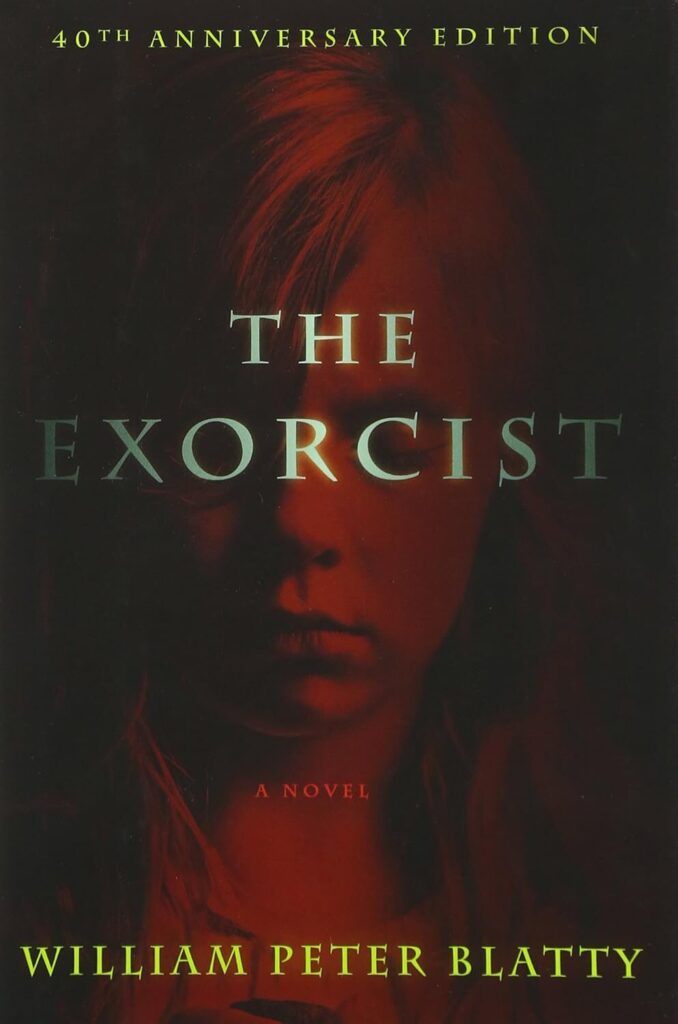

Loving the Repulsive – The Exorcist

In our recent episodes on The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty, I spent a lot of time discussing the theology and religious context of the novel. I chose to focus on this because of the impact the novel and the movie have had on religious belief and belief in the paranormal. This focus on what Blatty got wrong took away from some of the things that Blatty got right. In this blog post, I’d like to spend some time examining the complicated role that love plays in the exorcist, particularly the love of that which repulses us.

For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life.

– John 3:16, King James Version (bad translation, but great prose)

This is an oft quoted passage of the bible. It encapsulates in a single verse what many Christian’s would say is the essence of their faith. It clarifies that Christ’s sacrifice on the cross was an act of love for all humanity, and an invitation to enter into The Kingdom of God. Whether one is a Christian or not, this is a powerful statement. Imagine a truly divine being: all knowing, all powerful, all good. Ignore any philosophical criticisms you may have of this concept for a moment. Imagine that being loves you. Imagine that being loves you so much it would sacrifice itself for you, and not just you, everyone you have ever encountered. It doesn’t take long for our minds to start poking holes in this fantasy. Certainly not everyone is deserving of this love. How can you love me and the people who hate me? How can you love me and the people who hurt me, hate me, beat me, kill me? What kind of love is that? What good is that kind of love?

Human beings are not programmed for this kind of love. Those who turn the other cheek in the face of violence and freely give away all that they have aren’t often the winners of natural selection. Without the protection of others who have a more practical definition of love, humans who attempt to live in accordance with these higher ideals will not survive long. Despite this, on some level, most of us desire this kind of love. Libraries have been filled since the dawn of writing with the work of philosophers, monks, priests, and thinkers of all kinds pondering this very conundrum. Ultimately, “faith” is the belief that all of this effort to understand universal love, and to be worthy of it, is not a total waste of time.

To be very clear, I do not believe that Christians have a monopoly on universal love. Nor do I consider myself to be a Christian. Across the world there are multiple examples of enlightened teachers showing us that there is more to this existence than mere survival. With focused effort we can be better. We can live with more purpose and aspire to higher ideals. We can leave this world a little better than we found it. But first we must have faith that there is something more worthy of our effort than mere survival. We require a faith strong enough to override our instincts and to act in accordance with these higher ideals. The application of this faith and effort is what I would call “practice.” One common teaching across many belief systems is that practitioners should act with loving kindness and empathy towards even those beings that they find repulsive. It is much easier said than done, as Father Merrin states:

“Long ago I despaired of ever loving my neighbor. Certain people…repelled me. And so how could I love them? I thought. It tormented me, Damien; it lead me to despair of myself and from that, very soon, to despair of my God. My faith was shattered.”

Surprised, Karras turned and looked at Merrin with interest. “And what happned?” he asked.

“Ah well…at last I realized that God would never ask of me that which I know to be psychologically impossible; that the love which He asked was in my will and not meant to be felt as emotion. No. Not at all. He was asking that I act with love; that I do unto others; and that I should do it unto those who repelled me, I believe was a greater act of love than any other.”

-The Exorcist, pg 345-356

Merrin states that he believes that the purpose of this possession is not to kill Regan. The demon has higher aims than the death of one innocent. Regan’s death is an act of existential nihilism to counter any faith the observers have in the possibility of a higher power saving them. The demon wants us to believe that there is no point in trying. That we do not deserve salvation. That we are disgusting, low creatures; biological machines that exist only to ingest matter, excrete waste, and then reproduce so that it can be done all over again. In an effort to show this, the demon attempts to make Regan repulsive to our senses. He forces blasphemies and insults from her mouth. He uses his incredibly strength to physically attack those who try to help her. He forces her body to excrete every foul substances it is capable of producing. He puts on vulgar sexual displays. He even uses her body to murder a man.

In addition to these efforts at repulsion, the demon also uses its power to render all medical intervention ineffective. No earthly power can undo this damage. The demon is waging a psychological war on two fronts represented by our two priests. He attacks Regan’s worthiness of love, represented by Father Merrin’s personal struggle with the grotesque. He references Regan’s supposed murder of Dennings often in the presence of her mother and Karras. The purpose is to make them question if there is any coming back from what has already been done. The demon knows that Karras has become more psychiatrist than priest. Karras does not fully believe that this exorcism can succeed where medicine failed. All of this is an attack on their faith. Should the priests waver in their faith that Regan can be saved, and deserves to be saved, they will fail.

Ultimately the priests do succeed, though it costs them their lives. I have issues with this ending that I discuss in depth on our second episode. Ultimately, I’m not convinced that Father Karras ever really overcame his lack of faith. He was given proof of the supernatural. It was not love that guided his spiritual awakening. It was intellectual curiosity. Karras abandons The Rite of Exoricism, and invites the demon to take him. In the story, he does this because Regan will likely not survive long enough for the rite to be completed, but it muddles the message.

Whatever qualms I have with the messaging, Blatty manages to touch on something very interesting in Merrin’s speech on the purpose of possession. Merrin has dedicated his life to trying to follow the example of Christ, but deep in his core he has been unable to feel the love that we are told God has for the world. It is not his ability to feel this love, but rather his desire to feel it and his willingness to act with faith that this love can exist, that matters. This is a poignant insight.

The theme is foreshadowed in Karras’s own statements about when and where he feels God’s love. When a piss-soaked bum drunkenly begs Karras for his last dollar, Karras struggles to feel anything other than revulsion for his fellow man. He does give the man the dollar, but only out of a sense of obligation. He feels no love in the act. Later, when counseling a new priest who is struggling with the isolation of priesthood, Karras takes the young priest to a hill to observe the sunset. He laments that he used to come up here to feel the presence of God. It’s easy to find God in a beautiful sunset. It’s a bit harder to find God in a filthy alcoholic begging you for money. Karras doesn’t need to find the divine in the disgusting, though. He simply needs to have faith that it is there. Again, easier said than done.

I’ve come back to this thought a lot since I finished my reading of The Exorcist. I’m not a Christian, but I have my own beliefs and practices. As I’ve gotten older, I feel that I’ve grown a little more empathetic to my fellow human beings, even the ones who repulse me. Certainly I’ve grown tired of fighting. I’ve never struggled with the grotesque. Maybe that’s why I’m able to embrace the horror genre so readily. I have a strong stomach for fluids and chunks and gore. These are not the things that repulse me.

Ideologies repulse me. The ones I struggle to love are the ones who enthusiastically cheer on cruelty, so long as it’s happening to the out-group. I struggle to love those who foment conflict and division. Those who harm the vulnerable for their own gain. In my mind, it is righteous and good to be repulsed by people who embrace these attitudes and behaviors, and yet it is also detrimental to hate those people and treat them with nothing but spite.

When I was young, I was angry. I’m certain that I hated more than I loved. Much of the behavior, belief, and rhetoric that I hated back then I still disapprove of now. As I’ve gotten older, though, I’ve softened my hatred. As cliched as it may sound, I am now able to believe that hatred doesn’t work. Like Father Merrin says to Father Karras, this may seem obvious to you, dear reader, but there was a time where it was not obvious to me. I was told that hate was wrong, but deep down I believed that it was entirely reasonable to hate what I believed was evil.

Like Father Merrin, I eventually faced a crisis. I did not have a crisis of faith. I had a genuine nervous breakdown. In order to heal, I had to let go of the anger and the hatred. I found that I quite liked Buddhist teachings. I established a meditation practice. I tried to act more in accordance with the Buddhist precepts. I also did a lot of therapy and got on medication. My mental health improved. I’ve tried my best not to lose my patience with the people who I find repulsive. I’ve tried to treat them with respect and kindness despite not feeling like they deserve it. Though I didn’t have the same faith that Blatty did, I put my faith in the idea that love was better than hate and communication was better than force.

I’d like to say it worked. I’ve personally changed more minds with calm conversation than I ever did with heated argument. In spite of those small wins, the world has gotten objectively worse for most people in my lifetime. But I wonder if maybe that isn’t the metaphorical demon trying to convince us that humanity is hopeless and not worth saving. It’s tempting to think that all this practice and effort is delusional and that it would be wiser to focus on accumulating power and goods to survive the end times. I guess at the end of the day, I’d just prefer to live in a world where universal love is possible. Even if we’re not capable of experiencing that kind of love, I think we could do worse than to have faith that it can exist.