The Anarchist Appeal of Cyberpunk – Virtual Light

William Gibson’s Virtual Light was released in 1994. Also released in 1994 was Netscape Navigator, the first internet browser to combine text with inline images. It was a time when businesses that bothered to have an internet presence at all advertised their America Online keyword before they advertised their URL. The Internet was young. The barrier to entry was still high. The userbase was still largely technical or hobbyist early adopters. The distributed nature of the network and the speed at which information could travel across vast physical distances sparked dreams of a secondary digital world where information was currency. Many saw the potential for a stateless, anarchic utopia.

In 1994, Tim C. May released his Cyphernomicon FAQ, outlining the beliefs and goals of the cypherpunk movement. It called for, among other things, the development of digital cryptocurrencies. In 2025, at the time of writing, one bitcoin is worth ~$90,000, and it couldn’t be further from achieving May’s anarchist goals of a decentralized currency. Tim May was no mere crypto-bro. He was an engineer at Intel who identified the way in which the natural radioactivity of clay was causing bits to flip in integrated circuits. He was a true believer in cryptography as a tool to protect freedom of speech. He believed, correctly in my opinion, that the internet could be made unregulatable, and that this was a good thing. He likened the right to cryptography to the 2nd Amendment Right to Bear Arms. This libertarian or anarchic ethos was at the heart of many early internet communities, and it was certainly at the heart of the literary cyberpunk movement.

Cyberpunk, as a genre, is often characterized as dystopian. It often depicts capitalism run amok. Our information, our bodies, our very consciousness is commodified by corporations that have grown to truly eldritch proportions. Common themes examine what it means to be human in an increasingly digitized world. Stylistically, cyberpunk borrows heavily from noir pulp fiction novels by the likes of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. In these novels, morally gray characters navigate a gritty, urban underworld. Anything can be had for a price. Any trace of optimism or altruism is quickly stamped out by street-smart hustlers. The ultra-wealthy can buy relative comfort and safety in the nice part of town, but no working person could ever hope to rise to that echelon of society.

Class division is a key feature of both noir and cyberpunk. The lines between corporations, criminal enterprises, and political states have been blurred until there is essentially no distinction between one and the others. Cronyism, nepotism, and financial corruption run rampant at all levels of society. Noir protagonists are often anti-heroes. They aren’t trying to save the world. They’re just trying to survive it.

I’ve heard cyberpunk stories, with their cynical noir influence, described as stories that warn of how society could become dystopia, but they don’t offer any recommendations for how to prevent it. The more I’ve thought about that sentiment, the more accurate I think it is. I also think that societal collapse may be the very reason that people love it.

Being something of a cynic myself, I don’t think all “bad” outcomes can be avoided. One day, everything will end. It doesn’t matter to the universe how horribly you suffer or how brilliantly you shine. With that said, though, I don’t think William Gibson is quite so hopeless about the future. He sees potential beyond the collapse.

In Virtual Light, we have a stock standard noir MacGuffin hunt, but we also have The Bridge. In the far future of…2006…an earthquake has rendered the Golden Gate Bridge unfit for traffic, and it has sat abandoned ever since. A series of spontaneous protests leads to a community of people slowly developing a functional, permanent shanty-city along the bridge. The Bridge, as this community comes to be known, exists entirely outside of the law. Despite a total lack of regulation or police presence, the community functions surprisingly well. Almost a third of the book is dedicated to conversations between a Japanese sociologist, Shinya Yamazaki, and the man who arguably founded the settlement, Skinner.

Without the need for labor, capitalists and governments have turned their backs on the surplus population. The middle class has vanished. Those who are not rich have fallen into abject poverty. With social safety nets and modern employment removed, people have returned to what some philosophers would argue is a more natural state. An unplanned community has evolved without a clear hierarchy from a need for companionship and the mutual benefit of all members. When something breaks, someone fixes it. If there’s work to be done, someone does it. If someone creates value for others, they’re rewarded. If someone harms the community, they could be expelled.

Yamazaki is fascinated by The Bridge. He is in love with the culture and the architecture. He views it from an aesthetic perspective as an example of a living Thomasson. This bridge and these people are vestigial relics of a bygone age. The “main” society no longer has any practical use for them, and yet they persist. Despite having no “purpose,” they have become beautiful in their own right, a form of hyper art.

Yamazaki doesn’t initially focus on the sociopolitical implications of The Bridge. He represents Osaka University and is trying to adequately describe The Bridge to parties who are deeply entrenched in the corrupt hypercapitalist system of the “main” society. Those establishment parties think of The Bridge, at best, as art. It is a curiosity, something for the wealthy to gawk at and admire and study. It’s the “real” San Francisco that the ordinary tourist doesn’t get to see. As the interviews with Skinner progress, though, it quickly becomes apparent that The Bridge isn’t just a Thomasson.

The Bridge is an example of an anarchist society that has come about, not through revolution, but through natural evolution. This population did not reject authority, but rather, they had been rejected by authority. It is a secondary society that has evolved from the failure of the old. It is not planned. It is not controlled. It is not glamorous. But in a way, the people of The Bridge are freer than the people trying and failing to stay afloat in the hyper-capitalist main society.

We are come not only past the century’s closing, he thought, the millennium’s turning, but to the end of something else. Era? Paradigm? Everywhere, the signs of closure.

Modernity was ending.

Here, on the bridge, it long since had.

He would walk toward Oakland now, feeling for the new thing’s strange heart.

-Gibson, W. (n.d.). The Modern Dance. In Virtual Light.

The Bridge represents something new. Something distinctly postmodern in the most literal sense of the word. Gibson is showing us a light at the end of the capitalist tunnel. From the ashes of the corporatocracy, there could rise new societies without the need for owners and rulers.

Gibson is channeling the hope that many in the early hacker movement had for the internet. Following is an excerpt from the legendary essay “The Conscience of a Hacker.”

This is our world now… the world of the electron and the switch, the

beauty of the baud. We make use of a service already existing without paying

for what could be dirt-cheap if it wasn’t run by profiteering gluttons, and

you call us criminals. We explore… and you call us criminals. We seek

after knowledge… and you call us criminals. We exist without skin color,

without nationality, without religious bias… and you call us criminals.

You build atomic bombs, you wage wars, you murder, cheat, and lie to us

and try to make us believe it’s for our own good, yet we’re the criminals.

Yes, I am a criminal. My crime is that of curiosity. My crime is

that of judging people by what they say and think, not what they look like.

My crime is that of outsmarting you, something that you will never forgive me

for.

I am a hacker, and this is my manifesto. You may stop this individual,

but you can’t stop us all…

Blankenship, L. (n.d.). The conscience of a hacker. Phrack. Retrieved from https://phrack.org/issues/7/3.

Early hacker writings were filled with this sort of angsty, rebellious sentiment against The Establishment. If the powers that be were not competent enough to stop the hackers, then maybe they were not competent enough to be powers any longer. Knowledge and technical skill were seen as the great equalizers. May the best hustle win.

Hacker communities were built around mutual interests. Individuals came together to exchange ideas and techniques. Friendships were formed. Contracts were made. Favors were exchanged. Like with The Bridge, there were no leaders. The individuals involved might never even know the real names or identities of their collaborators. It was egalitarian. It was anti-authority. It was punk.

I write this blog in the year of our lord, 2025. I graduated from high school in 2006, the same year in which Virtual Light is set. I grew up with cyberpunk. I saw all three Matrix movies in the theater. I went into computer science partially because I loved the old school BBS and IRC culture of the 90’s. I didn’t want to be a hacker, but I was a big fan of the open source software movement. I believed in the communal development of non-profit products for the good of society. I naively expected that by pursuing a career in computer science, I would become a participant in a culture of like-minded individuals. I have never been more wrong.

I have worked for major corporations. I have worked for smaller corporations. I have worked in product development, consulting, production support, and a few other areas. I have written software for healthcare, government programs, and financial institutions. I have been doing this professionally for more than 10 years. I have been immersed in computer culture for a very long time. It has changed. If anything, I now think cyberpunk was too optimistic.

The punks are long gone. The dream of an egalitarian, anarchist utopia without borders, boundaries, or hierarchies is well and truly dead. The internet has become a conglomeration of social media, curated by algorithms designed to feed us more of the same. The highest goal one can aspire to is becoming the CEO of a venture-backed start-up. Corporate and state interests have buried the hackers under a mountain of Big Data and co-opted the weapon that was designed to destroy them.

I regret my career choice every day of my life. I wish I were exaggerating. It has been utterly soul-crushing to witness what “tech” has become. The cryptocurrencies that Tim May believed would free individuals from government and financial institutions turned into meme coins and scams, championed by the very institutions May hoped to insulate himself from. The new heroes of the tech world are idiot capitalists wielding generational wealth to steal unimaginable swaths of data for all manner of anti-human purposes.

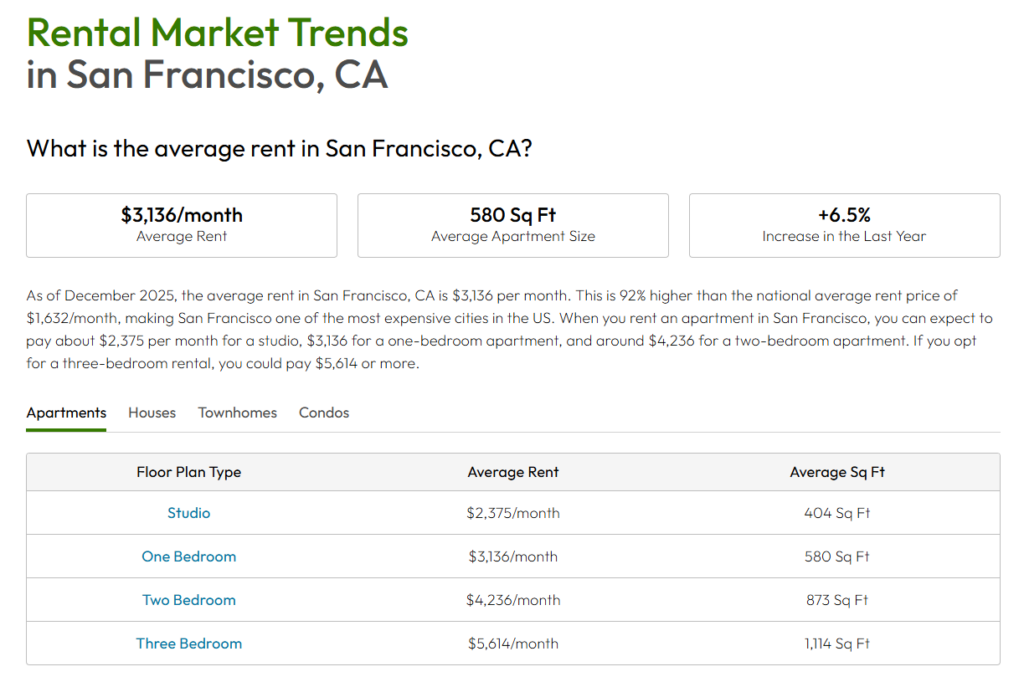

In 2025, I would be ecstatic to see the Golden Gate Bridge transformed into affordable housing, rather than being a parking lot for cars, each sporting a bumper sticker proudly proclaiming which senile psychopath they voted for. In 2025, I sit here stubbornly writing blogs on my own website rather than on Medium or Substack, partially as an act of futile rebellion against the homogeneity of the modern internet. No one will ever read these posts. No algorithm will ever favor them. It took me years to get to this point, but honestly, I prefer it this way. I’d rather shout into the void than engage with another fucking “platform.”

I can’t help but think that cyberpunk scratches a similar itch to zombie stories. Both genres are filled with horrible dystopias where people suffer every day, but there’s a little part of us that envies the freedom of the survivors when they’re not actively fighting for their lives. When we acknowledge that society is broken beyond fixing, we’re finally allowed to give up and just live as well as we can for as long as we can. We no longer need to worry about creating engaging user experiences to milk data and money from people whose lives we’re trying to economically destroy with automation.

I think in 1994 Gibson saw the writing on the wall. This hacker movement was already being co-opted by the very establishment it thought it was outsmarting. The stock market grows even as poverty increases. The middle class is going to drown in a sea of AI-slop. When the Elon Musks and Sam Altmans of the world have finally gutted the economy and abandoned us to our fate, at least we’ll finally be free of them. We may wind up living in huts made of scrap metal on a bridge, but we’ll have each other. God willing, the billionaires will be content to swap AI-generated images of bored apes with each other until the sun burns out, and we won’t have to hear from them again. I’m excited to get on with the business of surviving.